Ever since it was announced, Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer has been among the most awaited cinematic events across the world – and rightly so. The film brings a smorgasbord of sensory and intellectual experiences. High on emotion, innovation, ideology, ethics, drama, and sheer brilliance (pun intended).

As Nolan’s films often do, Oppenheimer compels the viewer to think hard and introspect. So, albeit another drop in the ocean, here’s my take on Nolan’s newest.

(Spoilers ahead)

First things first

It’s tough to beat the standards when you are the standard. But Nolan cuts through the predicament like a hot knife through butter. He weaves a tightly knit screenplay; and sets it at a lightening pace. Arguably too quick in parts, the narrative remains relatively easy to comprehend.

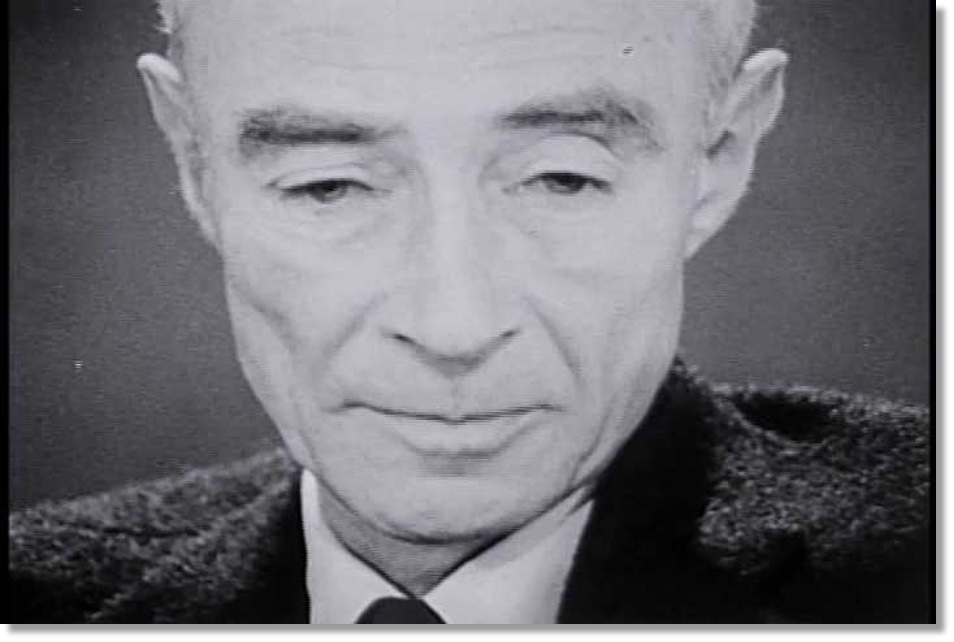

Needless to say, the auteur’s handiwork is incomplete without his coterie of stars. Cillian Murphy is devastatingly good as the titular character. He aptly captures the latter’s genius, charisma, passion, and most important, his gnawing sense of regret.

The supporting cast is chock full of talent – boasting Oscar winners and nominees like Kenneth Branagh, Florence Pugh, Emily Blunt, Matt Damon, Casey Affleck, Rami Malek, and Gary Oldman. It’s no surprise then that the film is a powerhouse of riveting performances.

Hoyte Van Hoytema’s camerawork is a feast for the eyes. The visual effects, showcasing atomic activity and explosions, appear realistic, hypnotic, and terrifying. Nolan also cleverly infuses black and white film to demarcate the objective narrative from Oppenheimer’s subjective perspective. Not to mention a hauntingly powerful score from Ludwig Göransson, complementing the tapestry of stunning visuals.

Dilemma and Dharma

While it undoubtedly remains unique, the film is centered around a Nolan staple : the conflict between right and wrong, good and evil. This time though, the underlying moral dilemma is more visceral. To annihilate or be annihilated, that was the question.

During the battle of Kurukshetra, Lord Krishna guides Arjuna when he finds himself unable to slay his kin. The young prince is taught that dharma (duty) is paramount. All else is illusion. As a warrior, Arjuna’s duty was to fight. It was their respective karma that led the Pandavas and Kauravas to Kurukshetra. Now, it was for Arjuna to win the battle – even at the cost of fratricide. Lord Krishna’s teachings are encapsulated in the Bhagvad Gita.

J. Robert Oppenheimer was faced with a dilemma not too different from Arjuna’s. The Nazis were making a nuclear bomb. Their success would spell doom for all humanity. So, Oppenheimer decided to beat the Nazis to it. But there’s a chance the bomb would incinerate the entire world. Dropped in combat, it would vaporise scores of innocent civilians. How then, does he reconcile his mission with his conscience?

Like Arjuna, Oppenheimer too may have turned to Lord Krishna’s guidance in the Gita. Perhaps he considered it his paramount duty to defend his country. That all his achievement and suffering – his karma – had led him to the Manhattan Project. It was then his duty to see it through. Indeed, after the Trinity Test, he famously proclaimed, “Now I am become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds”. This is where Oppie’s genius descends, albeit momentarily, into self-aggrandisement.

While being implored to focus on his duty, Arjuna is told that he would simply wield the weapon. He is simply the instrument. The Kauravas are already dead. It is He who creates, He who causes, and He who kills. He is Brahman (not to be confused with Brahmin). It is in this backdrop that Lord Krishna takes his celestial form to show Arjuna that He is Time (or Death), the Destroyer of Worlds. The Gita’s words are referenced below:

Chapter 11, Verse 32

śhrī-bhagavān uvācha

kālo ’smi loka-kṣhaya-kṛit pravṛiddho

lokān samāhartum iha pravṛittaḥ

ṛite ’pi tvāṁ na bhaviṣhyanti sarve

ye ’vasthitāḥ pratyanīkeṣhu yodhāḥ

Translation

The Supreme Lord said:

I am mighty Time, the source of destruction that comes forth to annihilate the worlds. Even without your participation, the warriors arrayed in the opposing army shall cease to exist.

(Source: https://www.holy-bhagavad-gita.org/chapter/11/verse/32)

Oppenheimer strays from the path of Arjuna; arrogates unto himself the role of Lord Krishna. He forgets, in the moment, that he too is merely a vehicle. A tiny cog in the cosmic wheel of cause and effect. Indeed, right after the Trinity Test, Oppenheimer is effectively stripped of all his powers. He has no access to the fate of his own invention. It belongs to people who neither share Oppenheimer’s ideals nor his intellect. Hitler is dead, the Nazis defeated – all without developing an atomic bomb. Despite the dissipation of Oppenheimer’s motivating force, the US drops not one, but two atomic bombs on Japan. Their blood, on Oppenheimer’s hands.

That said, Oppenheimer was a hero in the US. He could well have lived out the rest of his days as a celebrated war hero; perhaps even bagged a Nobel prize. However, he used his celebrity to steer policy away from nuclear proliferation. Despite the foreseeable backlash, he strenuously opposed the development of a Hydrogen bomb; advocated against the use of any nuclear weapon in combat. A lesser person could well have acted differently.

The authorities do not take this lying down. Oppenheimer’s security clearance is revoked in a closed-door, non-judicial, and palpably lopsided proceeding. He is forced to give up all government positions. Despite the futility of his participation in the security hearings, Oppenheimer voluntarily subjects himself to the humiliation. He knows what he deserves, and embraces his fate. Perhaps his learnings from the Gita – of duty, action, and consequences – never left him after all.

Albeit more than five decades following Oppenheimer’s death, redemption arrives in 2022 when US Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm nullifies the earlier decision and restores his security clearance.

Interestingly, Nolan’s conscience seems quite clear. He remains against the glorification of war. He omits shots of the bombings at Hiroshima or Nagasaki. No grand explosions. No mushroom cloud. No visuals of Japanese faces melting or buildings crumbling to ash. Nolan does not afford us any satisfaction – cinematic, sadistic, or otherwise -from Fat Man and Little Boy.

What if?

From a cosmic perspective, one might say that all possible knowledge already exists. It only awaits discovery. On this planet, (so far) only humans have the ability to make that discovery. From that lens, perhaps the atomic bomb was always in existence. Oppenheimer and team were only the first to discover it. If not him, another physicist would have harnessed mankind’s most terrible weapon. The Nazis, the Soviets, the Japanese, the English, or the French – could have been anyone.

Would the world have been better off if the first atomic bomb had been detonated by another State or at another time? Does the lack of a favorable alternate answer justify the US’s decision to massacre innocent civilians? One’s guess is as good as another’s.

Demos of dismay

All other questions aside, even according to the security hearings, Oppenheimer was decidedly a true patriot. Did he ever ponder, though, if patriotism was a two-way street?

Early on, when Oppenheimer is on a recruitment drive, he is warned that their kind (scientists) is needed until they aren’t. Oppenheimer simply brushes off the remark. He is confident that the sheer importance of his contribution to his country would cloak him from unscrupulous attacks from his own countrymen. That he could air his views with impunity. Unsurprisingly, he ends up smeared with all kinds of accusations – from infidelity and communism, all the way to espionage and treason. Genius, as a character in the film notes, does not guarantee wisdom.

History is rife with men like Oppenheimer, Scipio Africanus, and Alan Turing, who remained heroes only till they were useful to society; swiftly disgraced or cast out thereafter. Whereas others, like Christopher Columbus and Winston Churchill, remain glorified by society despite their horrific legacies.

Yet, many continue to persist in their duty towards the same society. Oppenheimer was perhaps one of them, or at least he thought he was. A life of duty and love of country, irrational as they may be at times, remain integral to human identity.

Parting words

Oppenheimer was an incredibly nuanced personality. Nolan’s film is an equal counterpart. Think what we may of Oppenheimer, but think we must. The moral quandary that plagued him first, plagues us all today. The world has enough nuclear weapons to blow up the Earth several times over, and then some. Nations, as recent events bear witness, remain more prone to war than ever before. Duty and country remain at the forefront of political discourse.

In this backdrop, Oppenheimer perhaps leaves us with one existential question: when it’s nuclear war at hand, to whom do we owe our dharma (duty) – to country or humanity?

Food for thought.

Leave a comment