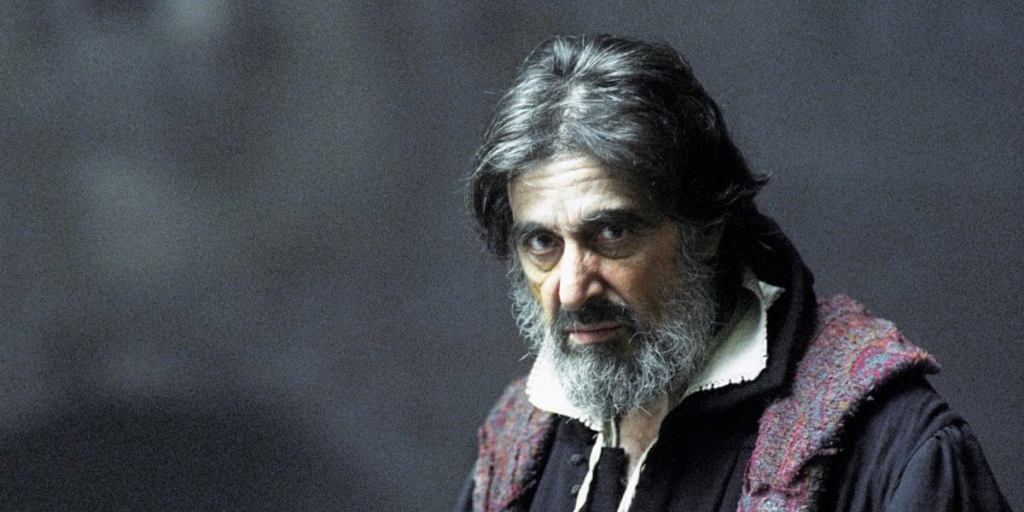

Shylock is possibly the most polarising character ever created by William Shakespeare. A Jewish moneylender, Shylock mercilessly pursues the pound of flesh promised to him as collateral for a loan. For Antonio, Shylock’s borrower and the titular Merchant of Venice, this means certain death.

At first blush, it is difficult to see Shakespeare’s portrayal of Shylock as anything but flat and anti-semitic. However, a closer look may reveal finer layers under the surface of the Bard’s most controversial play. These aspects, and almost every other aspect of Shakespeare’s life and work, have been analysed, scrutinised and dissected by scholars for over four centuries. This is not an academic inquiry of the sort, but a set of reflections on Shylock and the notion of justice in The Merchant of Venice (“MOV”).

Background

Bassanio, a Venetian nobleman with dwindling fortunes, has his heart set on Portia, the princess of Belmont. He needs three thousand ducats to make the journey to Belmont; and he must arrive before another suitor wins Portia’s hand. Bassanio reaches out to his friend Antonio. Though happy to offer all his wealth, Antonio lacks the liquidity. Hence, they approach Shylock. The Jew will help on one condition: if Antonio defaults, he will pay with a pound of his own flesh. Bassanio protests. However, Antonio’s love for Bassanio far exceeds his hatred for Shylock. Antonio is also confident that his merchant vessels, sufficiently laden, will reach Venice well before the date of repayment. He accepts the bond.

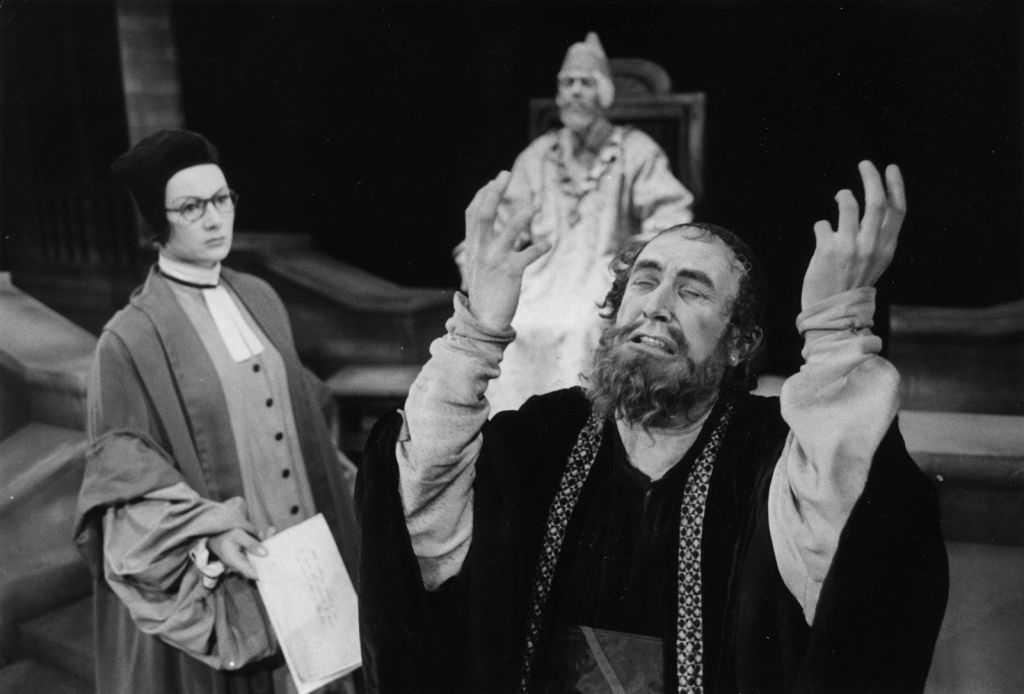

Soon after, in the midst of his nuptial celebrations, Bassanio learns that Antonio’s ships have sunk. Shylock calls upon his bond. Bassanio rushes to Venice with Portia’s blessing and ducats. Unbeknownst to all, Portia also arrives at the trial dressed as the male advocate Balthasar. The Duke allows her to take the floor as adjudicator at Antonio’s trial. Antonio confirms the bond. Bassanio offers to pay thrice the sum; but Shylock insists on the bond.

Venice takes contracts very seriously. Portia upholds Shylock’s bond as valid and binding. Just as Shylock unsheathes his knife, Portia asks him to tarry a little. She warns Shylock that he is entitled only to a pound of flesh – no more, no less. He cannot draw a drop of blood. Outsmarted, Shylock tries to settle for Bassanio’s enhanced offer. However, given his unwavering insistence on the bond, Shylock is refused even the principal.

Since Shylock is an alien, Portia finds him guilty of directly or indirectly attempting to take a Venetian life. As penalty, one half of his property is to be seized by the victim, Antonio. The other half must be surrendered to Venice. Shylock’s life is entirely at the Duke’s mercy, which mercy is swiftly extended. Antonio, too, is ready to forego his half of Shylock’s assets – on the twin conditions that Shylock convert to Christianity and, upon his death, bequeath all wealth to his daughter and Lorenzo, with whom she has eloped. The Duke also qualifies his pardon, issued previously, with Antonio’s conditions. Shylock has no choice but to accept. He leaves defeated and alone. After a minor hiccup, Antonio and the rest live happily ever after.

All’s fair in love and law?

About two centuries before the Bard was born, Edward I issued a royal decree in 1290 expelling Jews from the English Kingdom. The ban was overturned only in 1656, long after Shakespeare was gone. It is unlikely, therefore, that the Bard ever had a first-hand acquaintance with Jewish life. What he did have was access to Jewish stereotypes. He likely read The Jew of Malta, written by his contemporary Christopher Marlowe. Interestingly, the latter play features a Jewish character far more vicious and vengeful than Shylock.

If he wanted to, Shakespeare could well have presented Shylock as a more stereotypical and loathsome Jew. He could do so without facing any artistic, social or legal consequences. Instead, he conjured up a complex Shylock, arming him with a plethora of reasons to be bitter. Indeed, one of the Bard’s most powerful (and painful) monologues (“…Hath not a Jew eyes?…”) is assigned to Shylock.

That said, Shylock is no saint. He is so blinded by rage that all reason and mercy are drained from him. So much so that, quite contrary to Jewish stereotypes, Shylock even rejects thrice the bond’s value. He is not an ideal father, employer, banker, or person for that matter. He is flawed, and a bundle of contradictions – but hardly more so than the next person. He hates a Christian, but the hatred does not necessarily extend to all Christians. Though he knows all too well what it is like to be humiliated and systemically persecuted, Shylock does not suppress the urge to inflict the same humiliation on another.

Shakespeare does not spare the Christians either – even though his queen, country, and audience, all pray to Christ. Whether it is Antonio spitting on Shylock’s face, Lorenzo eloping with Shylock’s daughter and ducats, the countless insults the Venetians hurl at Shylock, or, in the guide of mercy, Shylock’s forced conversion to Christianity. The wholesale persecution and ghettoization of Jews in Venice also comes out starkly in MOV. Antonio and Bassanio end up surrounded by lovers, friends, and well-wishers. Shylock is left dejected and alone; stripped of respect, wealth, and faith.

MOV also represents a curious idea of justice. Antonio’s trial is hardly a paragon of fairness. Neither Shylock nor Antonio has legal representation. The only adjudicator on the scene, Portia, is the textbook example of a judge in her own cause. Her judgment is capricious. At first, she upholds Shylock’s right to Antonio’s flesh as valid under Venetian law. A few moments later, through a hyper-technical legal maneuver, the same right is transmogrified into the criminal offence of conspiring to murder a Venetian. When the bond was made, Shylock had no premonition as to the fate of Antonio’s ships. It is unlikely Shylock had anything to do with their sinking. Yet, Shylock is charged with conspiring to kill Antonio. It is almost as if Antonio’s trial (or Shylock’s, depending on how one sees it) is a cautionary tale from the Bard; that justice, no matter how fair in appearance, always hides a predisposition to favour the powerful.

The offense itself applies only to aliens. The Jews, who are very much residents of Venice, are treated as aliens. When the law itself is unequal and arbitrary, its correct application will also lead to injustice. The law then becomes a means to perpetuate the very division and oppression it was meant to prevent. Justice may be blind, but those involved in judgement can see; and they often do so with myopic or jaundiced eyes.

Concluding thoughts

Was Shylock a lens through which Shakespeare sought to examine the systemic oppression of Jews? Or was the character merely a means to capitalise on a unique dramatic opportunity? Only the Bard can tell. If he meant to elicit laughs and scorn at the expense of Jews, Shakespeare’s literary genius would be no excuse for his insensitivity. On the other hand, even if his intention was to be sympathetic, the fact remains that MOV does contain fodder for antisemitic elements.

Perhaps it does not matter what Shakespeare thought. Shylock is a mirror. He reflects and reveals what each reader makes of Shylock; of Jews and Christians; revenge and mercy; justice and morality. Shylock can be just as veritably reviled or weaponised as he can be empathised with. Perhaps, therein lies the crux of the Bard’s everlasting genius.

—–

Leave a comment