(Photo credits: https://www.renemagritte.org/#google_vignette)

The world is made of words and wonder. Write ‘pen’ on paper and the mind involuntarily thinks of a writing instrument. An elongated cylindrical device filled with a dark-coloured liquid, metallic tip at the nose, will conjure in the head. With it will gush in the physical attributes we associate with writing. Sounds obvious? Not to René Magritte (21 November 1898 – 15 August 1967).

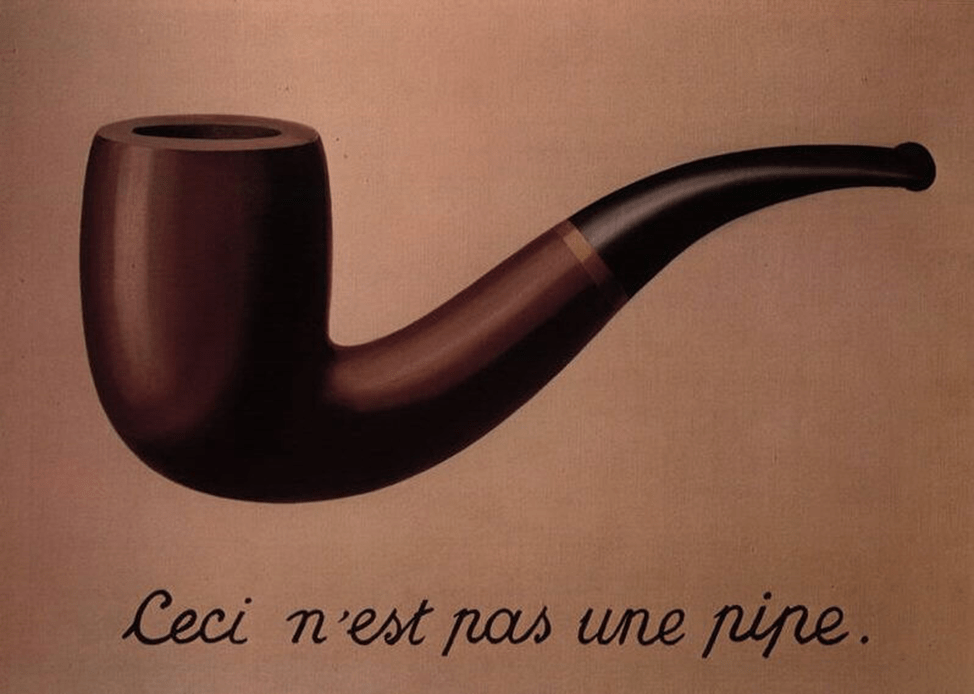

The Treachery of Images (This is Not a Pipe) (La trahison des images [Ceci n’est pas une pipe]), Belgium, 1929

The painting looks rather simple. A smoking pipe painted over French for ‘This is not a pipe’. But it doesn’t seem to make sense. It is, indeed a pipe, isn’t it? Well, Magritte would say it’s only a picture of what we generally identify as a pipe – not a real pipe. One cannot smoke the painted pipe. This may sound terribly obvious and, to some, even pretentious. However, such criticism may not be entirely fair. For most critics, the purport of the painting is obvious only in retrospect. More importantly, they miss the underlying thought – that things are not as they seem. Paint the map of any democratic nation over ‘this is not a democracy’. Would this be incorrect? Or entirely accurate? Either way, it wouldn’t be obvious.

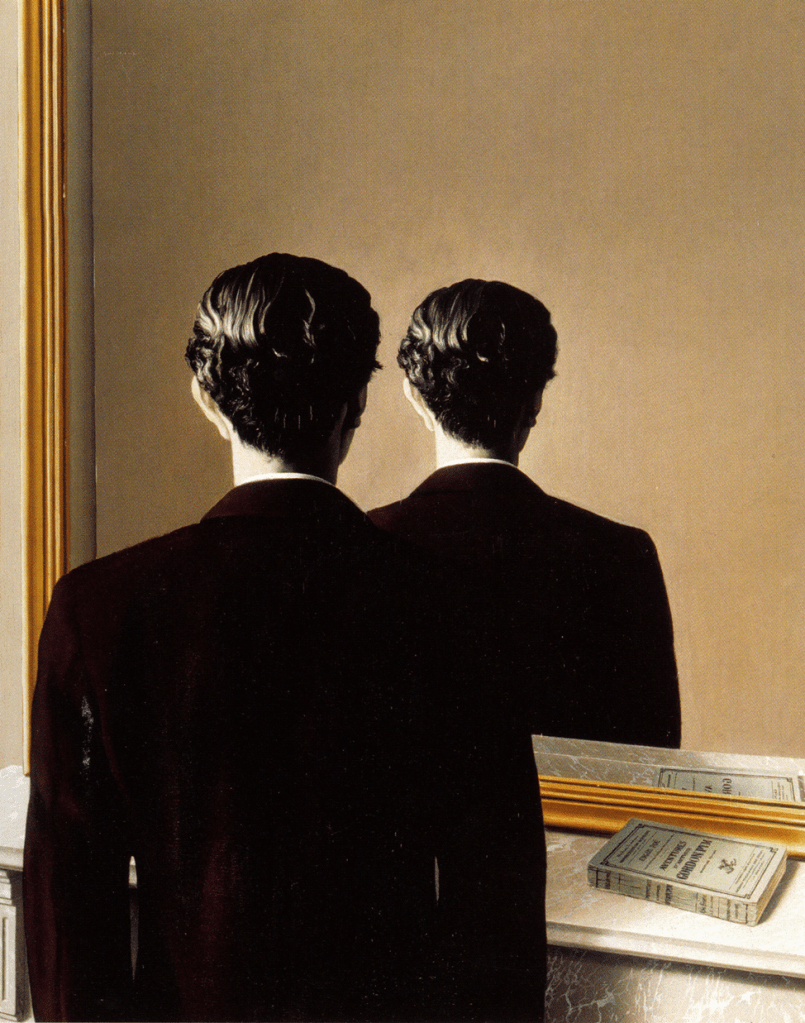

Magritte questions the certainty of the nexus between words, their meaning, and their visual representation. His work often loosens the grip language and reality have on the viewer’s mind. Some of his paintings can jolt the viewers out of their intellectual slumber, reminding the viewer to think about thinking. Others reflect Magritte’s fascination with all that is hidden. ‘Not to be Reproduced’, is one that does both. The reversed image of Edgar Allen Poe’s ‘Adventures of Gordon Pym’ reveals a mirror in the frame. Facing the mirror is a young man in a flawless dark suit, his back towards the viewer. He lacks any motion or gesture. Perhaps his face can speak to the viewer. The mirror, however, only reproduces his back. His face remains hidden. Any chance at identification or physiognomic assessment is robbed. The young man, ever so close to the viewer, will always remain a mystery.

René Magritte. La Reproduction interdite (Not to Be Reproduced). Brussels, 1937 (https://www.moma.org/audio/playlist/180/2381)

Magritte was highly skilled in the academic sense, with an enviable grasp of light, color, and perspective. He was also unusually versatile; producing excellent works of impressionism, futurism, and cubism before arriving at his own unique style.

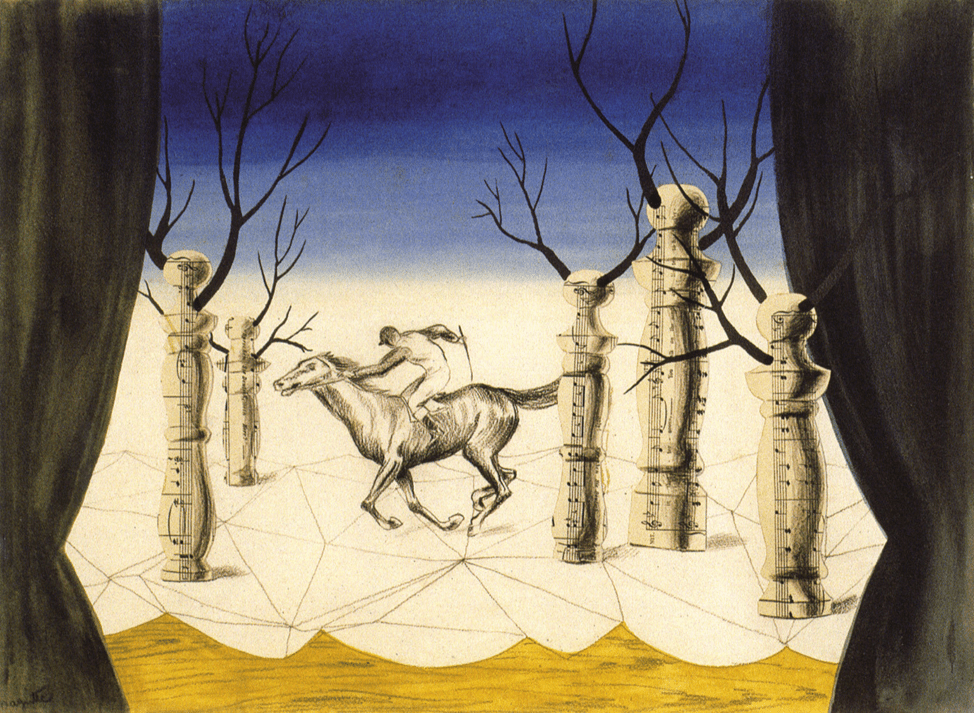

Many identify him as a surrealist; with the Lost Jockey (1926) Magritte’s first fray into the genre.

René Magritte. Le Jockey perdu (The Lost Jockey). Brussels, 1926, https://www.moma.org/audio/playlist/180/2374

Even so, it may not be fair to pigeonhole the modern master. Most of Magritte’s works seem anchored in reality; but he uses ‘realism’ mainly to express his subversive ideas. His subversion is not random. It’s not abstract, provocative, or experimental for the sake of it. He uses subversion to create visual poetry, luring his viewers into to an altogether different way of thinking.

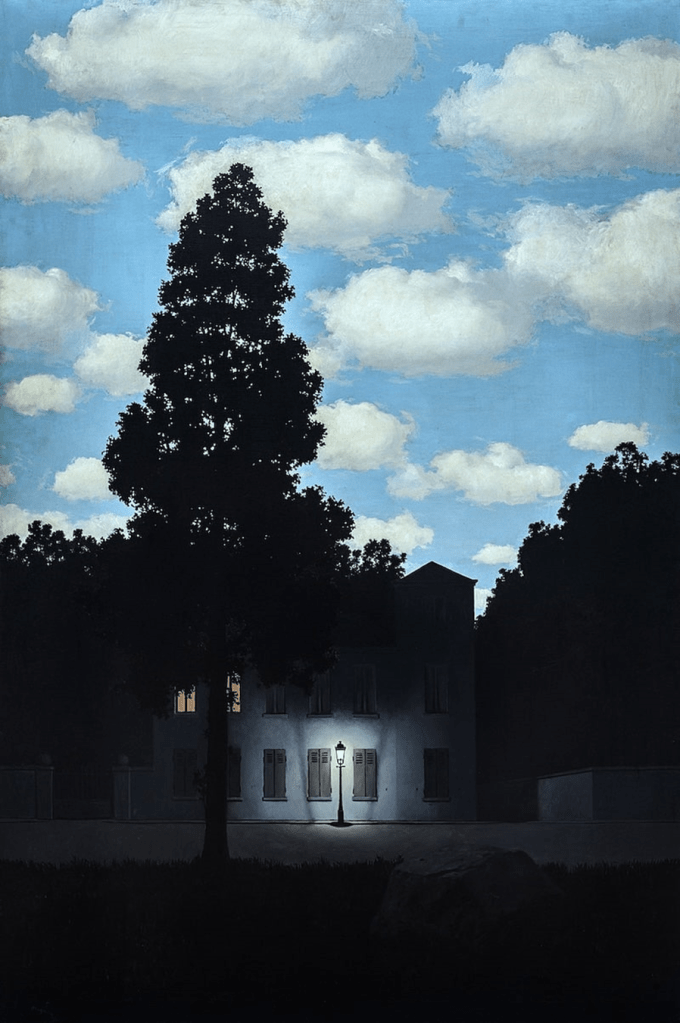

Here’s Magritte in his own words: “I have reproduced different concepts in ‘the Empire of Lights’, namely a nocturnal landscape and a sky as we see it during the daytime. The landscape leads us to think of night, the sky of day. In my opinion this simultaneity of day and night has the power to surprise and to charm. This power I call poetry.” (Marcel Pacquet, Rene Magritte: Thought Rendered Visible, Taschen, 2012).

The Empire of Light, Brussels, 1954

Magritte’s works are a unique symphony of beauty, skill, and original thought. Having produced more than 350 works during his lifetime, Magritte was as prolific as he was talented. Even today, his works are refreshing and relevant. One may or may not enjoy them all, but René Magritte’s works (and way of thinking) certainly make for a tempting exploration.

-Ritvik Kulkarni

Leave a reply to Ritvik M. Kulkarni Cancel reply